Children's writing provides a wonderful insight into the concepts of conventional writing that children are currently coming to understand, have already mastered, or are still working to fully grasp. Early elementary teachers understand how important inteoducing and encouraging appropriate writing attitudes and practices with our children.

According to a University of Arizona professor, Kare Foley Cusumano, there are seven concrete ideas that teachers should always remember and embody in their classrooms regarding writing experiences. These points include:

- Praising writing by the meaning that a child intends, and its content. This means never pointing out errors regarding conventional writing norms

- Understanding that inventive spelling/writing will develop into conventional writing

- Focusing on positives, not errors; avoid a focus on "correctness"

- Introducing conventional writing ideas by pointing them out in literature, environmental print, and personal letters

- Demonstrating writing by example: let children be involved in writing letters, emails, making grocery lists, writing checks, etc.

- Incorporating rich writing experiences into family activities like writing letters to family members, journaling, making cards, etc.

- Creating a World Wall or Spelling Dictionary for children, which they create and should not be used as an excuse to demand conventional spellings

When a teacher completely understands and carries out these ideas and philosophies of writing in her classroom, she has begun to develop the "best practice" and most appropriate environment for writing, but it is not yet complete! A child needs a supportive community in order to be the most successful in writing. A child also needs family and community support, which should be aligned with the 7 best practices identified by Cusumano. Teachers have a responsiblity to educate families and community members about the ways to approach writing literacy at home. Some great times to educate families include open house, parent-teacher conferences, and writing workshops. During these times, a teacher should look to convey the 7 integral philosophies of children's writing, and provide positive strategies for practicing appropriate writing at home.

Some simple ideas to encourage appropriate early writing at home include:

- Reading good children's literature, while pointing out conventional points like spacing, periods, syllables, beginning-middle-ends, left to write orientation, etc

- Encouraging writing with materials to write on and with

- Focus on the positives of writing, never what a child is missing

- If you cannot read inventive spelling, ask the child to read to you what he wrote

- Write letters, journal, lists, notes, anything!

- Demonstrate writing practices to start conversations

- Be creative, stay positive, model well, and be open!

Using these tips a teacher should be able to create a team of support for a child so he can develop appropriate and flourishing writing habits and attitudes.

As an Early Childhood educator, I am constantly investigating and researching new approaches, perspectives and ideas about literacy acquisition and development. This blog explores various articles, opinions, classroom evidences, and personal experiences. I aim to educate intentionally, effectively, and appropriately; continually updating curriculum with new practices is always necessary, and welcomed.

Sunday, January 29, 2012

Sunday, January 22, 2012

Digging for Early Literacy

Children learn and absorb literacy experiences constantly throughout their lives. This natural process is harshly and dramatically contradicted in traditional teaching methods in elementary schools. We expect children to conform to worksheets, word walls, memorization, speed reading tests, and spelling tests when these assessments and requirements oppose how children learn best: through experience. A great way to create this experience and encourage natural literacy acquisition in children is by creating a “Literacy Dig.” A Literacy Dig is a full, rich, and wonderful method to set up a classroom to boost literacy practices. To initiate the Literacy Dig, a teacher should search for some sort of outside community connection that could enrich the child as a whole. An example that a group of teachers and I are currently working on starts with a Goodwill store. We plan on starting the experience with a “field study,” where we will bring our students to Goodwill equipped with clipboards for notes, drawings, and recorded environmental print; cameras for videos and pictures; audio recorders; and plenty of writing utensils. At Goodwill, the children will try to document as much information as possible to bring back to the classroom. When back in the classroom, we will share our artifacts, notes, and pictures, speaking about these processes. To move the process further, we plan on encouraging the children to create their own “Goodwill” in our classroom/school. This will require planning for a wide range of relevant, real-life situations and the children will be using, developing, and acquiring literacy skills during the entire month(s) long process. Teachers can prearrange for members of the community to come into the classroom to share knowledge about the finance of running a Goodwill store, the environmental benefits of thrift shops, an owner of the store to talk about the business of hiring and managing employees, a banker to demonstrate how to ask for a loan to start the store, and many other community members. Then, with their new knowledge, the students can begin to form their store with very specific and accurate representations. A Literacy Dig like this has endless possibilities and can only be taken as far as the teacher is willing to run with it. A wonderful, involved, and spontaneous teacher can make a small idea like creating a Goodwill store a quarter-long event that covers all the curriculum and required standards. This is a great way to encourage, teach, and make meaning of literacy with children.

Tuesday, January 17, 2012

Thoughts on Culture in Literacy

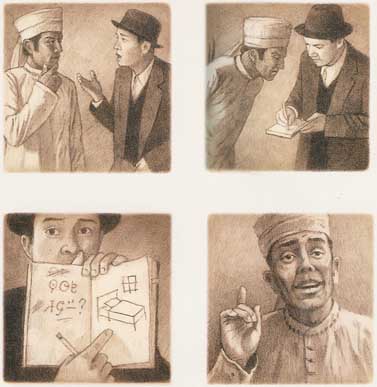

After recently watching a wonderful interpretation of Shaun Tan's Arrival, which can be watched by following the link, I gained a new perspective on teaching second language learners and educating children from various cultures and countries. Tan's novel, which is not completely shown in the YouTube video, follows a man as he throws himself to a completely foreign and new country. He experiences new customs, language, and interactions. These differences limit him from being able to have a job, except from a mindless factory job. Tan's thoughts pretty accurately reflect our view on immigrants in America. We seem to have this underlying idea that if English cannot be sufficiently spoken, a person's worth diminishes. When thinking about our students in our classrooms, do we hold these same biases? Should our English language learners be required to take assessments in English, or provided opportunities in their native language. It is a debate that is hot in education today. Tan continues his story, outlining the bitter struggles the man endures, but eventually he is able to earn enough money to send his family so that they join him in the new county.

The man's language abilities are not seen as worthy of holding a non-factory job, and the question of "what it means to be literate" can be pondered through this story. If we say that literacy is a means of communicating, then this man is literate in his own sign language and his native language, but not the countries main language. Is he literate? Are our second language learners literate if they cannot speak English, but achieve milestones in their first language? These types of questions need to be considered when thinking about teaching literacy in early education. Our own thoughts can be reflected in the manor in which we teach all types of learners. Thinking about establishing an inclusion setting, a community-based model in the classroom, and an anti-bias approach in my classroom, I can only come to the conclusion that requiring English language learners to solely communicate literacy in English is wrong. As teachers, we can think of creative and innovative ways to connect the first language to the classroom in a meaningful way.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)